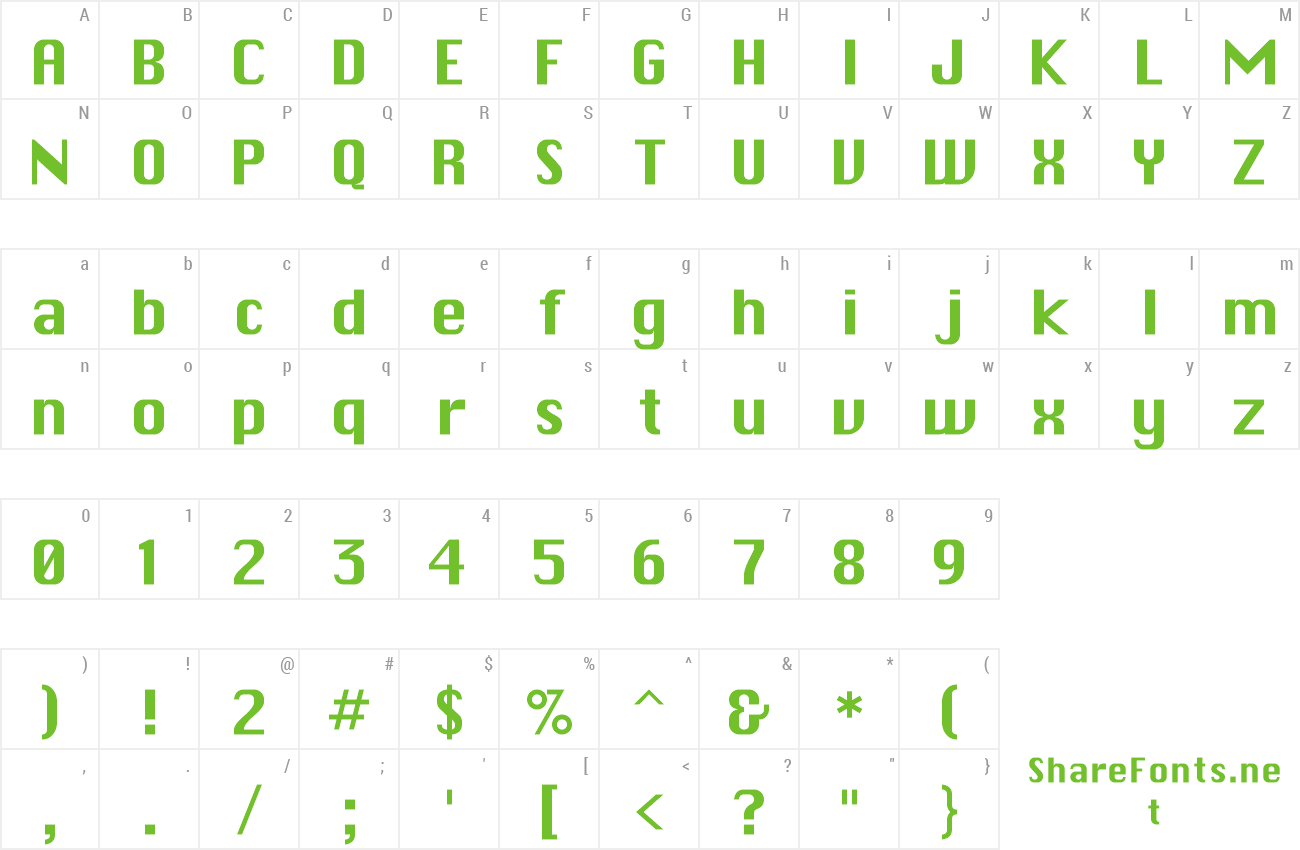

She created the characters on a prototype Mac before the first model hit the market in 1984 operating within the constraints of a low-resolution display, Chicago consisted exclusively of vertical, horizontal, and 45-degree elements - it had no round edges. “Chicago was designed specifically for use in menus and title bars,” she says. Kare, then a relatively green graphic designer, sought to create a typeface that would amp up the Mac’s user-friendly aesthetic. But the Macintosh, she adds, was novel in that it “allowed for proportionally spaced type, so fonts on the computer could more closely resemble traditional letterforms.” It was one of the earliest signals that Mac computers were not only for the people, but designed by them, too. “An ‘i’ and an ‘m’ occupied the same horizontal space, unlike typeset or handwritten letters,” Kare says.

When Kare joined the Macintosh software group in 1982, computer typefaces were primarily monospaced, meaning each character had the same width. Not only was it inextricably linked with Apple’s brand identity in its early years, but it was also groundbreaking in the world of digital typography. Designed in 1984 by Apple’s in-house graphic designer Susan Kare, the Chicago typeface was intended to boost screen readability. This was a time when people largely viewed computers as jargon-filled robots, and Apple aimed to position them as user-friendly portals to alternate universes. It was the operating system’s first typeface, and its name was Chicago. Perhaps you can envision that thick, jagged, sans-serif typeface, even if you can’t identify it. When you pressed its power button, its home screen would greet you with the message, “Welcome to Macintosh,” the glow of technology embracing you like a familiar friend. Decades before the sleek MacBook Air I write this on even existed, Apple introduced its original Macintosh personal computer, a woefully khaki-colored, boxy desktop machine.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)